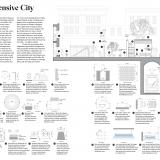

Defensive City

Mark Magazine #59 December 2015/January 2016

The age of fortressed cities is long gone. Protective borders designed to fend off outside enemies have made a shift from city perimeters to national and even supranational boundaries, as in the case of the Schengen Area.

Defence measures adopted by today’s cities mainly target the enemy within. The most visible elements of the defensive city are aimed not at terrorist attacks or crime, but at ordinary citizens. ‘Unwanted behaviour’ is the accusatory term used as a basis for the employment of such elements, and because unwanted behaviour is not yet a crime, preventative measures are the only way to ban it. Not only spray-painting a work of art on a wall is seen as unwanted behaviour, but also lying down, sitting, standing in a group and walking: activities that take place in public space – the same space that is advertised in real-estate brochures as vivid, dynamic and bustling with life.

It’s a battle of realities. The ‘general public’ does not want a Saturday morning at the shops to be marred by the reality of homeless people, or to see the vomit spewed by their own kids the day before congealing in the corner of their favourite store. But the same general public likes being part of the image of an open, welcoming and unconstrained city. Thus the smaller and more inconspicuous the city’s protective elements, the better. Park benches with armrests at 50-cm intervals seem pleasant and thoughtfully designed, until you get tired and try to sleep on them. Little metal brackets along the edges of pavements look like ornaments but are, in fact, anti-skating devices. Opera music played outside a clothing store appears to be a sophisticated touch, but it’s meant to hinder youngsters who might want to hang out there. In our electronic future, designs will get smaller and ever more virtual. Crowd scanners, as well as motion and position detectors, have already been tested. It won’t be long before an intelligent pavement tells you to get up and walk – no spikes needed.

It’s the city government that implements preventative designs, but only by popular demand. The defensive city is the Western, capitalistic city – a clean and bloodless construct that works optimally only until shops close. Statistically, though, we feel safer. The question is: are we willing to exchange feeling safe for being more alive?

Text and graphics Theo Deutinger, Stefanos Filippas, Vasiliki Mavrikaki and Eliza Mante